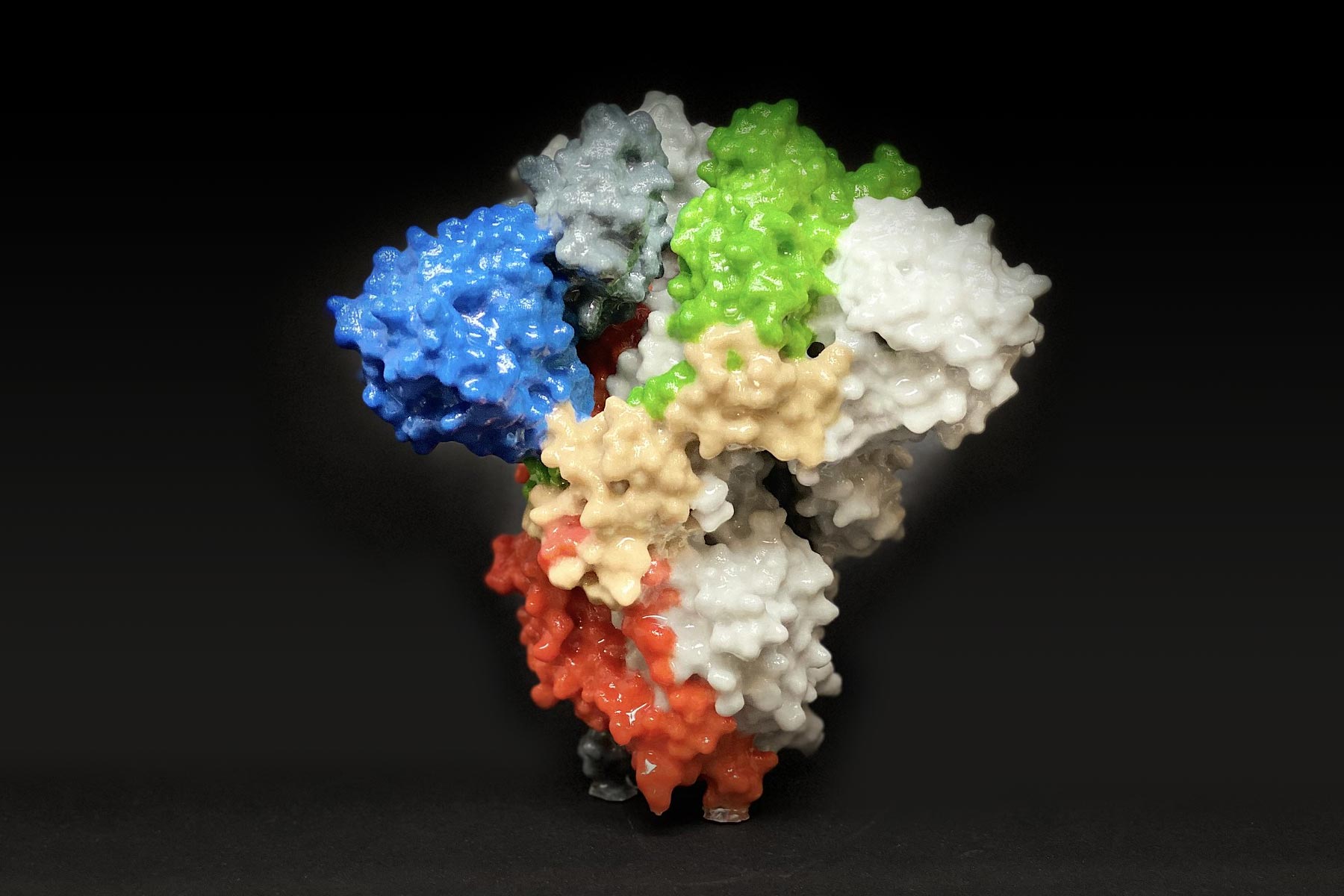

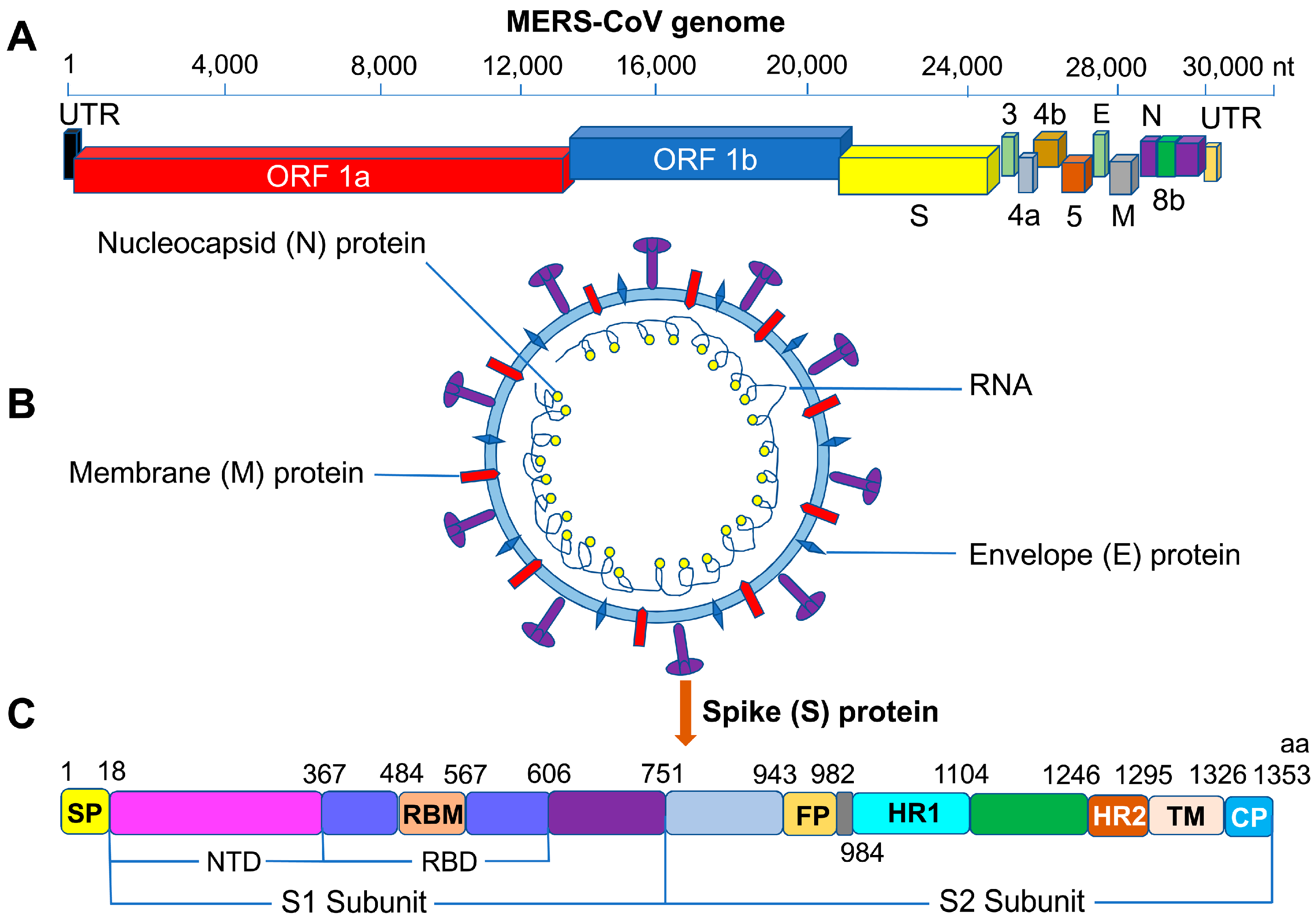

This is why new mutations that alter how the spike functions are of particular concern – they may impact how we control the spread of SARS-CoV-2. Another way would be to make the spikes “stickier” for our cells. One way this could occur is through a mutation on a part of the spike protein that prevents protective antibodies from binding to it. But some may cause changes that give the new version of the virus a selective advantage by making it more transmissible or infectious. Most mutations will not be beneficial and either stop the spike protein from working or have no effect on its function. Encoded within the viral genome, the protein can mutate and changes its biochemical properties as the virus evolves. One of the most concerning features of the spike protein of SARS-CoV-2 is how it moves or changes over time during the evolution of the virus. The SARS-CoV-2 virus is changing over time. Production of the spike inside our cells then starts the process of protective antibody and T cell production. Given how crucial the spike protein is to the virus, many antiviral vaccines or drugs are targeted to viral glycoproteins.įor SARS-CoV-2, the vaccines produced by Pfizer/BioNTech and Moderna give instructions to our immune system to make our own version of the spike protein, which happens shortly following immunisation. The spike is also involved in other processes like assembly, structural stability and immune evasion. One of these functional units binds to a protein on the surface of our cells called ACE2, triggering uptake of the virus particle and eventually membrane fusion. There are estimated to be roughly 26 spike trimers per virus. The spike protein of SARS-CoV-2 is stuck on the roughly spherical viral particle, embedded within the envelope and projecting out into space, ready to cling on to unsuspecting cells. The spike protein is made up of different sections that perform different functions. The spike can be subdivided into distinct functional units, known as domains, which fulfil different biochemical functions of the protein, such as binding to the target cell, fusing with the membrane, and allowing the spike to sit on the viral envelope. Spike proteins like to stick together and three separate spike molecules bind to each other to form a functional “trimeric” unit. The spike protein is composed of a linear chain of 1,273 amino acids, neatly folded into a structure, which is studded with up to 23 sugar molecules. Ebola viruses have one, the influenza virus has two, and herpes simplex virus has five.

The spike protein of coronaviruses is one such viral glycoprotein.

.jpg)

In order to gain entry to the inside of the cell, enveloped viruses use proteins (or glycoproteins as they are frequently covered in slippery sugar molecules) to fuse their own membrane to that of cells’ and take over the cell. Like cellular life, coronaviruses themselves are surrounded by a fatty membrane known as an envelope. Pišlar A, Mitrović A, Sabotič J, Pečar Fonović U, Perišić Nanut M, Jakoš T, et al, PLoS Pathog 16(11), CC BY How SARS-CoV-2 gets into cells and reproduces.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)